1. Abstract art is the "grandfather" of comic book art. Why? Because both experiment with the idea of how to tell a story or depict something normal, like a pipe. Charlie Brown is a kid and not a kid; Superman is a man and not a man; both are abstractions of kids and men in other to symbolize ideas about both. Also, both forms use color, shapes, and style in innovative ways so that we can collaborate on what a work means and how we read it. In other words, depending on how we respond to the artwork, we'll all see a slightly different story--and have a different emotional response to it as well.

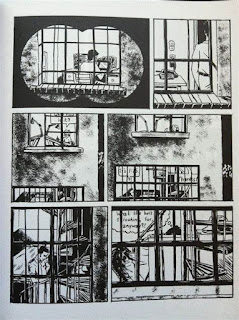

2. We look some excerpts from the book, 99 Ways to Tell a Story, which takes a simple template of a few frames (a guy getting up from his desk, being asked what time it is, and then going to the refrigerator to get something--only to forget what he wanted) and re-tells it 99 times, changing the style, perspective, and characterization. Here are two examples below:

Both of these relate to Superman: American Alien in how they take the same story (all of the comics in SAA are written by Max Landis) and by changing the artwork and the style, the story changes completely. This is the magic of comics: that we don't read stories, we read art. We're primarily a visual species, and even writing is a form of art that we read, interpret, and process.

3. We also discussed Frame Transitions, and how comic artists use the "gutter" (the space between frame) to make great leaps of imagination. Here are the basic kinds of transitions that you'll see in comics:

Action to Action: slightly larger acts of closure—usually cause and effect progression

Subject to Subject: about the same use of closure—moves from one subject to the next to advance the story

Scene to Scene: larger acts of closure—movement in time and space, so that ten years can pass between two frames, or the ability to show the same scene on different sides of the globe.

Aspect to Aspect: also more closure required—the “wandering eye” effect of showing different aspects of a place, idea, or mood.

Non-Sequitir: Latin for “it does not follow,” sometimes transitions involve connections that don’t make literal sense, but do within the context of the comic.

We looked at this frame from the comic/chapter, "Owl," as an example of how complex these transitions can get:

In this panel, we have two forms of storytelling crashing together. In the background, we see a typical progression of action to action, with each frame advancing the story a few seconds. It goes from Left to Right as a normal comic or book would. But juxtaposed on top of this is another 'frame,' though it's not even in a frame: it's a floating body of Lois Lane who is still talking, but has basically broken through the comic.

Behind her, even more strangely, is a stream of type-written words. With a little effort, we can figure out that the words are her application to the journalism program she and Clark are both in. This helps to give us some quick backstory to her character, without having to waste dialogue and time telling us about her. Also, by taking her out of the comic, it suggests that she's in a spotlight, the way Clark undoubtedly sees her at this moment. He's mesmerized by her. And she's very confident and fearless. It captures a quality we've all experienced, when we're interacting in the world, but our brain is doing something else entirely. Clark is beginning to fall in love with Lois at first sight, so to speak. So the comic is preparing us for this relationship.

Think about these ideas when you read our next comics, and I'll bring some new ones to the table on Wednesday. Take care and let me know if you have any questions!

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment